Those who know me best are probably wrinkling their brows in confusion right now. They know the full story behind the infamous “pot-o-eggs” dish mentioned in my bio. I cannot be relied upon to serve as anyone’s sous-chef. My knife skills are horrendous. When it comes to the art, science, and sport of cooking, I am best suited for the role of barstool spectator. Also taste tester. But I am probably the last person who should be dispensing any advice about cooking.

Even my daughter laughed when I told her the topic of this month’s post. (She keeps me grounded.) Her dad is our resident chef. Back in our college days, he gained a few years of experience working in restaurant kitchens which has served him (and me) quite well. He has excellent knife skills. He also seems to have a natural understanding of flavors and knows what ingredients will go well together. It’s a gift. He can rummage through our fridge and pantry, pull out various items, and throw together a quick and easy meal that also tastes good.

I, on the other hand, can only be trusted with dishes that require no more than just basic assembly: a bowl of cereal, buttered toast, peanut butter sandwiches. Sometimes I get creative with salad.

I can cook rice.

This wasn’t always the case. “Pot-o-rice” was an unfortunate sequel to “pot-o-eggs” before a friend taught me the foolproof knuckle trick. “What is the knuckle trick?” you ask. I’ll let you in on the secret, step by step.

First, pour your desired amount of rice into a pot. No need to measure. Just dump it right in there. Give the pot a little back and forth shake action to level it out.

Next, head to the faucet and run some water over the rice for a few seconds. Set the pot on a flat surface and let the rice settle back down along the bottom.

Lower the tip of your pointer finger into the water, aiming straight down, until it touches the top of the rice. (Don’t bury it in the rice.) The water should reach your first knuckle, about one-third the length of your finger. Not quite there yet? Add a little more water and recheck the level until it’s just right.

Place the pot over high heat until the water starts to boil. Reduce to a simmer and cover with a lid. 20 minutes later, you’ll have perfect, fluffy white rice.

Believe it or not, this is a one-size-fits-all recipe. It works for index fingers of all shapes and sizes. Adult fingers, that is. I have not tested this method on a child.

Other than for the occasional grilled cheese sandwich, or rice, I tend to avoid using the stovetop. I’m uncomfortable by all of the smoking and sizzling that can go on there. It’s too dangerous. I much prefer the oven because I can close the door and protect myself from whatever is happening inside. I can confidently roast vegetables just the way I like them, typically with just a little bit of olive oil, salt, and pepper. They are delicious on their own—or served over rice.

Somehow I can never seem to remember the appropriate temperature and duration for veggie roasting, so I have to google it every time. Recommendations tend to vary a bit; I usually go with whatever Ina Garten suggests. The Barefoot Contessa has never steered me wrong. For winter root vegetables (my favorite), bake at 425 degrees for 25-35 minutes. How easy is that?

Well, Ina, as I have learned from experience, sometimes even the simplest instructions can yield disastrous results.

In season one’s “London” episode of Netflix’s “Down to Earth with Zac Efron,” Zac visits Ella Mills (@Deliciouslyella), whose Sri Lankan vegan curry recipe sent my salivary glands into overdrive. It looked so amazingly delicious and yet surprisingly simple that I was inspired to rush out and purchase all of the ingredients in order to recreate the dish at home. All by myself.

Of course, I happily accepted my husband’s assistance with slicing and dicing the vegetables. (Knife skills, remember?) When it was time to preheat the oven, he asked me for the baking temperature. “200,” I answered. “Are you sure?” he asked dubiously. I double-checked the recipe and confirmed, “Yes, 200 degrees for 30-35 minutes.” He gave me a quizzical look but went along with it anyway, trusting that I was reading directly from the recipe. I may not be a very good cook, but I can read and follow directions just fine. (Um…) 200 degrees it is!

Wait. That’s not what the Barefoot Contessa would do.

No, it most certainly is not. (Alarm bells should have gone off for me here.) Because Ina lives in America, where we use the Fahrenheit scale, whereas Ella lives across the pond—in the land of Celsius. Ugh.

That’s right. In my excitement and haste, I somehow overlooked the capital C looming behind the 200 and neglected to apply the necessary conversion. 45 minutes later, our curry vegetables were nowhere near tender, leaving me perplexed and discouraged. My husband once more questioned the baking temperature, and suddenly that previously inconspicuous C became glaringly obvious. Son of a (expletive).

I felt utterly defeated. I was ready to throw in the towel and permanently ban myself from the kitchen, to toss the entire dish into the trash just as I had been forced to do with “pot-o-eggs.” But my husband knew better. He simply cranked up the oven to 425, and we let the vegetables continue to roast until tender. That curry dish was absolutely worth the wait, even with all of the hassle…and damage to my ego.

My aversion to cooking is largely due to my lack of experience. I haven’t invested any real time in developing skills that would help me to be more successful in the kitchen. I have no idea what I’m doing. Because I’m unsure of myself in the kitchen, I feel anxious, and that anxiety only increases the likelihood of my making a mistake. You know, like misreading directions or forgetting I’m not European.

Despite my many culinary failures, there have been a few times when I have actually enjoyed cooking. Looking back on those experiences, I noticed that they all shared certain similarities: music, a refreshing beverage, and prep bowls.

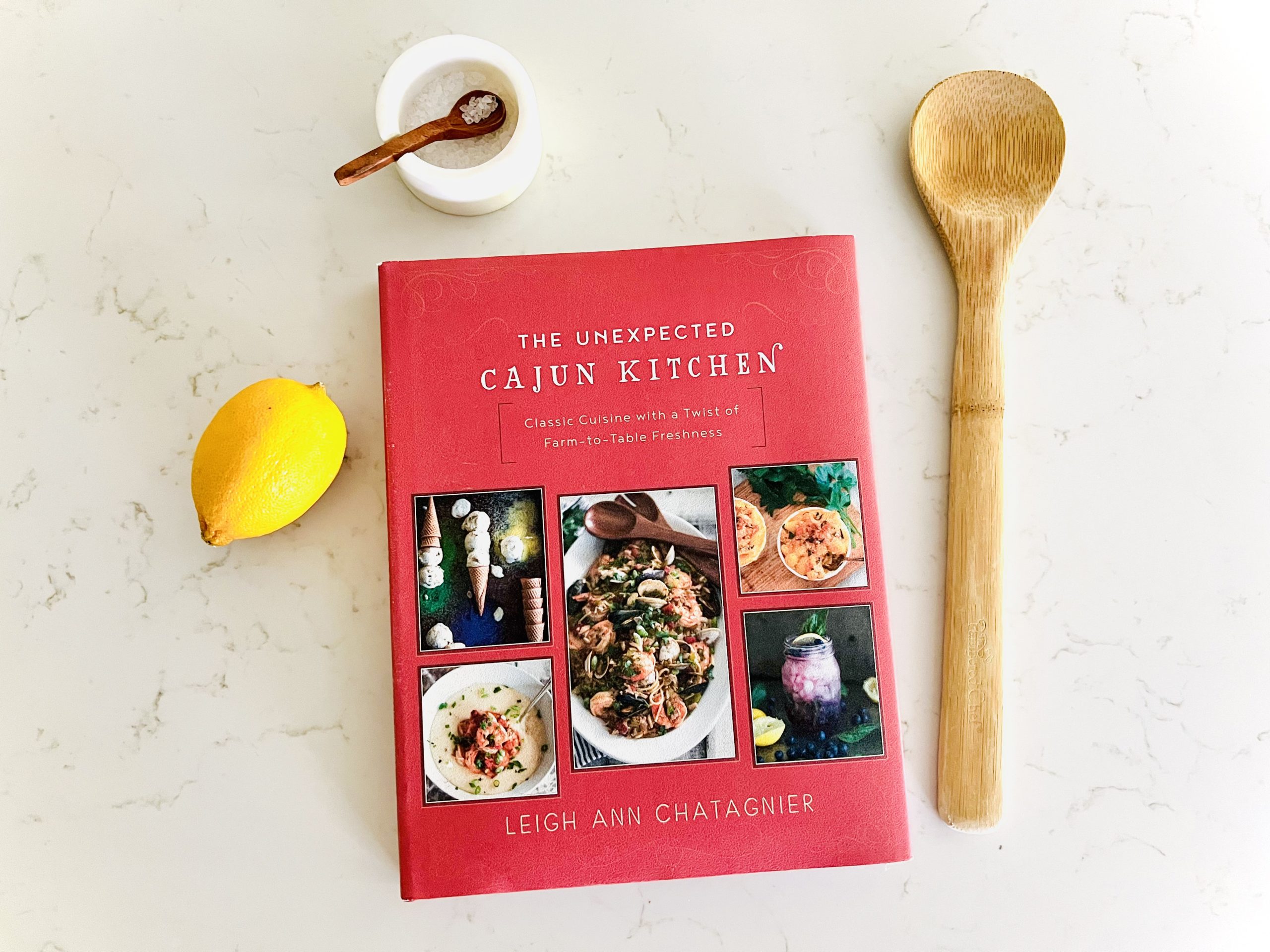

Ironically, I love cookbooks. Pretty ones. With a beautiful photo of each finished recipe. Every now and then, when I can take my time and not feel rushed, I’ll try out a never-before-attempted recipe from one of my cookbooks. Like this one:

Ambience is everything. Madeleine Peyroux is one of my favorite singers. Her bluesy-jazz tone is relaxing but not at all sleep-inducing. It’s hard to feel anxious while listening to French music. “Alexa, play Madeleine Peyroux.” And my cooking companion arrives.

I’m a planner and organizer by nature, so prep bowls are key for me. First, I familiarize myself with the recipe—every step and ingredient. Then I chop, dice, and grate everything. I carefully measure and separate each item, assembling an array of prep bowls lined up and ready to distribute their contents when the time comes.

I check and recheck every instruction, every measurement and abbreviation. Was it tsp or tbsp? 1/4 cup or 1/2 cup? I second and third guess everything, being extra careful to not make a mistake. But not at all in a harried way. On the contrary, I’m very relaxed. Why? And how, given my history? I repeat, ambience is everything.

With Madeleine Peyroux by my side, or in my ears at least, I leisurely sip on something sparkly and flavorful, like a glass of Belvoir Elderflower Lemonade or a nice prosecco. Maybe nibble on some cheese and crackers here and there. The whole cooking process is happening as a side act. I’m shifting the focus from what is usually an anxiety-inducing chore to distractions that I enjoy.

The process of achieving any goal is just as important as the achievement itself. I’m not aiming for a Michelin star here. I just want to put a plate of edible food on the table. Bonus if it tastes good. Sometimes it works out, sometimes not so much. I might as well make the learning process less daunting and more enjoyable!

Some of us know our way around the kitchen. The rest of us are really good at ordering takeout. The luckiest ones are married to someone who excuses their culinary ineptitude and graciously assumes the role of household chef without complaint—and has excellent knife skills.